posted 16 Sep 2003 at ucimc.org

"The problem with children, and with working class children in particualr, was that they refused to be integrated smoothly into an oppressive society. ...The child savers turned political problems into adjustment problems. Instead of seeking political solutions to the problems of young people, they chose therapeutic remedies, thereby deflecting criticisms of capitalism onto its victims." (excerpt)

Note from the one who posted this on ucimc.org:

While the focus of the following article is on the *poli-tricks* of juvenile "justice" from 1974, we can certainly garner valuable insights into the ways alleged "child savers" of today work their games.

Notably, the continuing and prevailing use of *emotionally potent oversimplifications* (which do better to hype people up and get them often quite uncritically implementing some policy which isn't up for discussing) is a most interesting and recurring phenomenon...Whatever topic about *children* you read in the mainstream (and often "alternative") press, we get this same pattern of hype first and foremost, and certain policies being implemented which turn out to go against our interests. Enjoy!The Child Savers: The Invention of Delinquency, by Anthony Platt; University of Chicago Press, 1969; Reviewed by Keith Hefner (FPS, December, 1974; p29-32)

Platt provides the historical background necessary for a truly radical critique of juvenile justice.

The people who worked to establish a separate juvenile justice system in the United States have typically been depicted as noble humanists, combining high ideals with practical zeal. They swooped down on our foul and fetid cities to rescue American young people from a life of crime and degeneracy. If it weren't for them, we would not be save in our homes tonight because juvenile delinquents would be roaming the streets looking for trouble.

That characterization of the "child savers" of early 20th century America has been repeated so often that most people believe it. A sprinkling of books published in the past 10 years (among them, Lisa Richette's The Throwaway Children and Lois Forer's No One Will Lissen) have begun to show that there is something drastically wrong with the juvenile justice system. They are usually filled with horror stories about long sentences for minor crimes and beatings in jail followed by pleas for more understanding, lighter case loads, and numerous reforms.

In The Child Savers, Anthony Platt takes us a step beyond the horror stories. He investigates the origins of the juvenile justice system and shows that the outrages of today are in many cases just logical consequences of the past. The child savers left a legacy of courts, prisons, new definitions of criminality, and new methods of "reforming" the young. But, he says bluntly, "the child savers should in no sense be considered libertarians or humanists." Critical research reveals that indiscriminate arrest, indeterminate sentencing, military drill, and hard labor were the concrete results of their reforms. And in most cases these were not accidental results--the child savers championed them.

Platt re-examines the child saving movement in this country, reviewing the motives, methods, and institutional results of the efforts of the self-proclaimed savers. His method of analysis is significant in that it does not automatically accept the criminality of the "offender." Instead, he shows why certain types of behavior were categorized as delinquent, and how the reformers attempted to modify that behavior. (Platt's method would be baluable in many areas, but it is particularly applicable in the area of juvenile delinquency. Over half of the crimes committed by young people in the U.S. are so-called status offenses--offenses like truancy, running away, and incorrigibility, which are not crimes for adults. Understanding how and why people are judged criminal is crucial to understanding who is a criminal.) Platt aplies his method primarily to a study of Illinois around 1900, because that is where the most influential and pioneering work on juvenile delinquency was accomplished.

Changing Views of Criminality

In the late 1800's and early 1900's the dominant opinion in criminology held that blacks, immigrants and many working class people were, in various ways, sub-human. They formed a "criminal class" which was incurably anti-social. Criminology concentrated on containment, and the biological origins of criminology were stressed. Sarah Cooper, who pioneered the kindergarten system in California, complained that many criminal children "came into the world freighted down with evil propensities and vicious tendencies. They start out handicapped in the race of life."

Such biological determinism was inconsisten with the practice of reform, and gave way to new theories which included the possibility of rehabilitation. The concept of the criminal was modified to suggest that the "natural imperfections" found in the criminal class could be remedied.

The first salient theories of childhood criminality were developed in this context. While the view of the young offender was greatly influenced by prevailing theories, it was less biologically deterministic. Children were less likely to be thought of as non-human or inherenetly evil. Christian ethics made it impossible to think of children as being entirely devoid of moral significance. Consequently young people were the first to benefit from the "new penology" of redemption: first because they were young and couldn't be held morally accountable for their actions, and second, because they were considered more malleable than older criminals.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The child savers could have articulated the criticism being acted out by the young people, and joined them to struggle against an unjust system. Instead they chose to mold them to fit that system.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------The Invention of Delinquency and Its Effects

Having provided that background, Platt askas what he considers to be the most important question. How was it determined that certain types of behavior were criminal, and what were the implications of those decisions?

He basically contends that the child savers took behavior which had previously been dealt with informally, such as begging, rowdiness, and disobedience to authority, and defined it as delignquent. The most important tactic used by the child savers to gain control over the lives of young people was to blur the distinction between delinquent and dependent young people. Originally there were two categories. Delinquent kids were those who had committed a crime, and were tried in adult courts and sentenced to adult jails. Dependent kids, such as street sellers and orphans, were generally ignored by the courts. The rationale for the blurring was that young young people who came into contact with the court or other agencies assigned to deal with them were being helped, not punished. Since they were being "helped" there was no need for procedural safeguards or constitutional protections. The behavior of young people was labeled and categorized. Then kids were stripped of their rights.

The state and various religious organizations were able, unfettered, to define dependence and delinquence as they saw fit. Standards for a "decent home" for example, were set so high that practically any young person could be declared independent. Poor and Black people, whose lifestyles didn't coincide with those of the child savers, were most likely to be found "in need of supervision." In addition, parents were allowed to commit thier children to the Illinois Reform School with the consent of the school's board of directors, and any "responsible member of the community" could turn in young women who they felt acted immorally. Enoch Wines, an influential authority on reformatories, proposed as early as 1870 that state authorities should take control of all kids who lack "proper" care or guardianship.

In 1870 the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that commitment without due process was unconstitutional (100 years ahead of the similar Gault decision), but child savers regarded the decision as "irresponsible." They ignored it; so did the courts. In 1882 the same court ruled that young women could be incarcerated without due process in the Illinois Industrial Training School for Girls because it supposedly wasn't a prison. The Court said:

We perceive hardly any more restraint of liberty than is found in any well regulated school. Such a degree of restraint is essential to the proper education of the child and is in no sense an infringement of the inherent right to personal liberty...

In short, almost any kid could be deemed dependent, and could be imprisoned for it. However, not any kid was sent to jail. It was mostly Black and working class people who did not conform to middle class values.

The Juvenile Court

The juvenile court is generally regarded as the child savers' most significant achievement. The juvenile court differed in many respects from the adult courts: the young person sent there was not accused of a crime, but offered assistance and guidance. Proceedings were informal, and due process safeguards were not applicable.

These courts, operating outside of constitutional structures, often intervened in cases where no offense had been committed, or investigated far beyond the scope of a particular crime, trying to determine a child's morality. For example, Platt metnions that a young person could come to the attention of the court for "posting a problem for some person in authority, such as a parent, teacher, or social worker." The other abuses stemming from informality and lack of due process in the juvenile court system today have been amply documented by many recent books, including the two mentioned earlier in this article.

Have Things Changed?

Platt is peesimistic about the current status of the juvenile courts. He feels that the "radical changes" predicted after the Gault decision are unlikely to materialize. "Important structural change depends on legislative reform" he says, but without elaboration. The practical result of Gault, he points out, is that lawyers are now being integrated into juvenile court proceedings. A study done in California showed that having counsel made little difference in delinquency cases, except that people who had a lawyer were more likely to be jailed pending trial. Adversary tactics are a long way off, and lawyers won't won't be in the forefront of pushing for them. Platt notes that public defenders are being brought into the juvenile court, and then goes into a lengthy discussion showing why they won't be very effective advocates of young people's rights. Lawyers view children's rights less favorably than the Supreme Court, and are more concerned with admonishing their client to tell the truth and shape up, than with winning the case.

Young People Disenfranchised

The most important political result of the child saving movement was that it actually restricted young people's freedom and autonomy. The child saver's rhetoric was about liberating children from the horrors of the city and the workplace, but the reality was tighter supervision and control by adults. Young people were removed from the jurisdiction of the adult courts, and taken out of adult jails, only to receive closer scrutiny and longer jail sentences from the juvenile court. The central interest of the child savers was in controlling and monitoring the behavior of young people--their recreation, education, values and attitudes toward authority. As Platt says, "their reforms were aimed at defining and regulating the dependent status of youth," not encouraging young people to take political power into their own hands to do what they thought would best serve their interests.

The child savers turned political problems into adjustment problems. Instead of seeking political solutions to the problems of young people, they chose therapeutic remedies, thereby deflecting criticism of capitalism onto its victims. The problems of young people were effectively removed from the political arena. Platt sums up "Young people were denied the option of withdrawing from or changing the institutions which governed their lives." The child savers solidified the dependent status of young people by disenfranchising them of their rights.

Adjustment Instead of Change

The problem with children, and with working class children in particular, was that they refused to be integrated smoothly into an oppressive society. The child savers could have articulated the criticism being acted out by the young people, and joined them to struggle against an unjust system. Instead they chose to mold them to fit that system. Platt says that Jane Addams, founder of Hull House and a noted child saver, admitted she was helping people adapt to a way of life which was oppressive and unjust. He cites another author who contends that it was well recognized that correctional workers were engaged in pacifying delinquents.

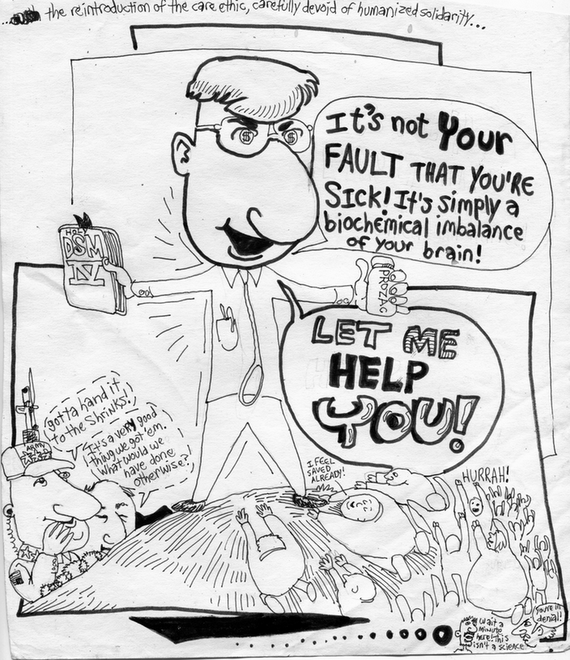

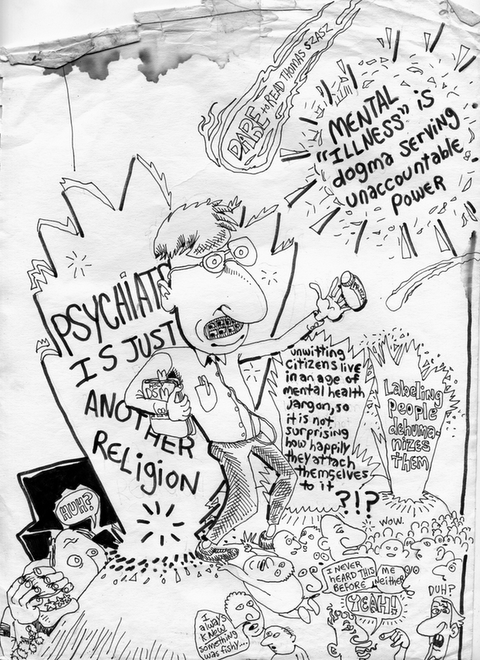

The child saving ethic still permeates contemporary programs. The paramount goal of most programs whether they are in juvenile correction, mental health, or inner city youth programs, is to help young people better adapt to this society, and few programs criticize what such adjustment means.

The Child Savers is an insightful analysis of the origins of American juvenile justice and their ramifications in today's society. Platt provides the historical background necessary for a truly radical critique of juvenile justice. In addition he appears to have a genuine respect for the right of young people to control their lives. That combination makes The Child Savers one of the most important books around on young people's liberation.